This essay is part of a new collection of work inspired by the anthology On Being Jewish Now: Reflections of Authors and Advocates. Want to contribute? Instructions here. Subscribe here.

Not everyone gets the chance to introduce their firstborn to their grandparents. On a summer’s day 30 years ago, we stood together in the driveway. Sid was nearly frozen from Parkinson’s disease, unable to navigate the stairs to my front door. I turned the baby’s feet towards him, and he beamed silently at my daughter’s sleeping face.

He died six months later.

Soon I will be in Dachau, following in the footsteps of my grandfather, Sid Olson. Sid was not Jewish. Nor was he a prisoner, or even a soldier. He was a journalist and a war correspondent.

I was lucky enough to know my grandfather well. I remember funny details about him: He wore glasses and soft wool sweaters. He had a wry smile and a bum knee. He liked gardening and golfing. Every night, he would plant his chair squarely in front of the television set, crank up the volume, and watch the news, drink in hand.

“Don’t be shy,” he once told me. “It’s a waste of time.”

I thought I had known him well, but what I didn’t know was that my grandfather—the man who had pushed me up and down the hilly front lawn in a wheelbarrow while I giggled with delight; the man who let me sit at his desk drawing princesses with long skirts and puffy sleeves—had seen mankind at its worst.

He had documented the collapse of the Nazi empire and had seen the horrors of Dachau concentration camp at the moment of its liberation on April 29, 1945.

He never told me.

I was in my mid-30s when my mother began sifting through her father’s archives, and discovered a sheaf of World War II dispatches he wrote for TIME and LIFE in 1945. I knew he had worked in advertising. I didn’t realize he’d also had an illustrious career as a journalist, rising from reporter to city editor at the Washington Post before joining Henry Luce’s TIME.

After my last child left for college, my mother and I began to go through the dispatches in earnest—organizing them, transcribing them, trying to understand their significance. I typed my way through the pandemic, and edited the manuscript, Following the Front: The Dispatches of World War II Correspondent Sidney A. Olson, while my mother lay dying.

As I worked—juggling research on fascism and genocide with cooking and laundry and kids’ games—I began to grasp what my grandfather had experienced in those final months of the war in Europe. I began to appreciate that, as a journalist, his job had been to witness and record, while attempting to mute his own emotional reactions.

Sid reported that thousands of displaced people streamed past his Jeep. Civilians who had been living underground emerged looking pale, in search of food and water. Cultural and historic sites lay in ruins. Like the buildings around him, civilization appeared to be collapsing before his eyes. He encountered evidence of rape, assassination, murder, suicide, starvation, even the theft of antiquities which—ironically—symbolized the height of man’s achievements.

Reading his dispatches, I had to stop every so often and look up, trying to wrap my head around the conundrum of being human. How can we be both good and evil?

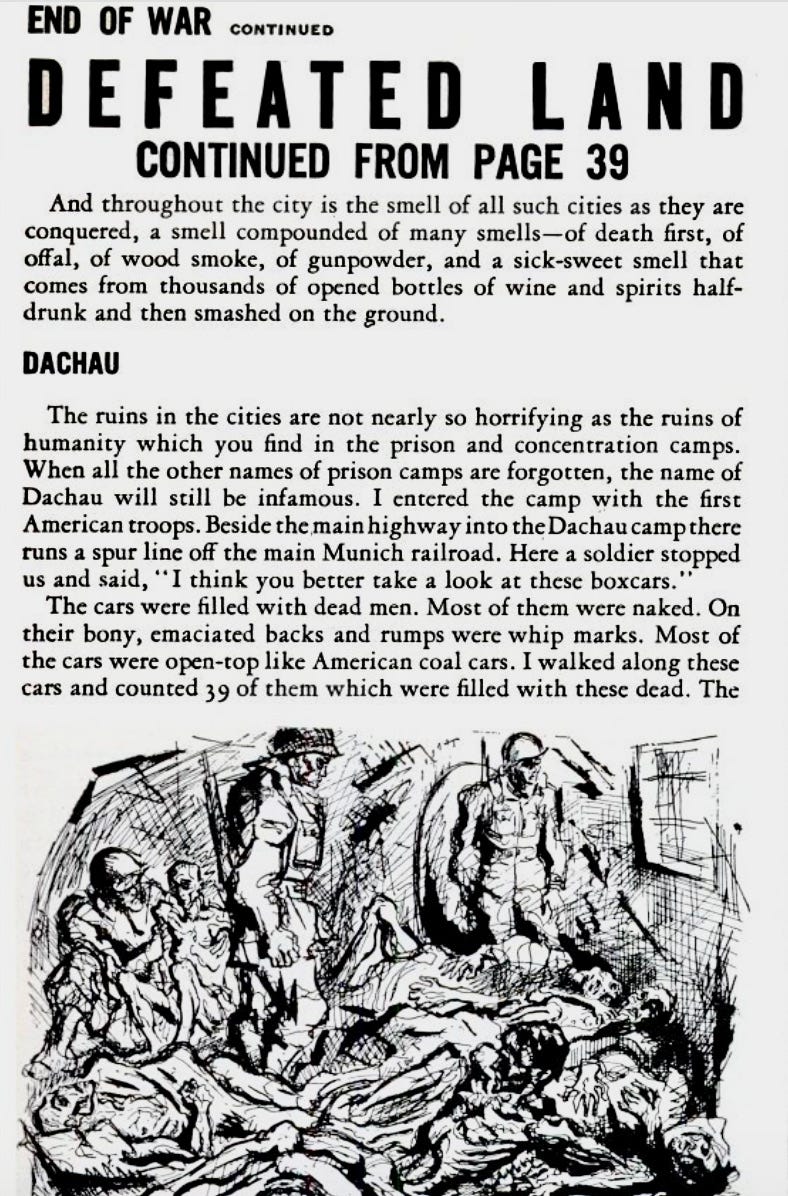

Because he wrote for a magazine, rather than a daily newspaper, Sid had the space and time to describe what he saw in granular detail. Dispatch 47 was 18 pages long and especially horrifying; it describes his journey through Dachau concentration camp when the gates were forced open on April 29, 1945.

Nothing had prepared him or anyone else for this harrowing day. Perhaps he was a bit better equipped than the American soldiers around him, most of whom were in their early 20s. Some were weeping and vomiting; others were stony-faced and angry; all were trying to regain their composure so that they could capture the guards, restore order to the camp and begin to help the survivors.

Sid returned to press camp in total darkness. He turned 37 at midnight, while he and his colleagues were still trying to find the right words to describe a level of suffering that had previously been unimaginable, and a level of cruelty which might not, in fact, have had a bottom.

Today marks the 80th anniversary of Dachau’s liberation. I will retrace the footsteps of my grandfather, and of those who survived—and of those who were robbed of the chance to meet their great-grandchildren.

Margot Clark-Junkins compiled and edited her grandfather’s WWII dispatches with her mother, Whitney Olson Clark. Following the Front: The Dispatches of World War II Correspondent Sidney A. Olson was published by Rowman & Littlefield in September 2024. She attended Mount Holyoke College and received a MA in Design & Curatorial Studies from the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. She writes a column called “Following the Front” for Substack and is currently at work on a book of short stories. Dispatch 47 can be read in its entirety in Following the Front.

Instagram: @margotclarkjunkins

This essay is part of a new collection of work inspired by the anthology On Being Jewish Now: Reflections of Authors and Advocates. Want to contribute? Instructions here. Subscribe here.

Thank you Margot for salvaging your grandfather’s tremendous work and giving it the recognition it deserves. I’m reading your Substack and looking forward to getting a copy of your book. What I have read so far is extremely well done. I know the rest will be superb and deeply moving.